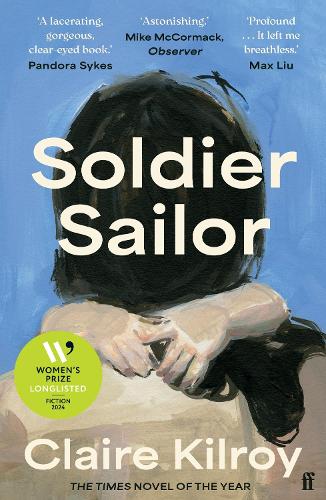

This book is not for me. I say that a lot in reviews when I can see objectively that I’m reading something good but it hasn’t quite clicked; in the case of Soldier Sailor, Claire Kilroy’s fifth novel, it’s even more deeply true. Every page, not for me, not speaking to me. Soldier Sailor is about early motherhood. We follow the stream-of-consciousness of a new mother, Soldier, as she addresses her beloved son, Sailor. The material here is familiar to anyone who’s ever read a Mumsnet thread: how marriages that once felt equal collapse into familiar patriarchal norms after a child is born, and Daddy is still free to do what he wants while Mummy is now expected only to care and serve (‘He had a big day ahead but I only had little days’, our narrator says bitterly). Kilroy, for my money, is strongest when writing about the upending nature of maternal love, the sheer otherworldly intensity of how much Soldier loves Sailor and how the world somehow makes this normal when it’s anything but. ‘I would kill for you… I would kill others for you, I would even kill myself. I would even kill my husband if it came down to it.’ Soldier returns obsessively to this theme, desperate to tell us about this kind of love: ‘I had wanted to know who [my husband] would save if there was a fire… “you can only save one of us and it has to be our baby”… I knew I would leave my husband behind in the fire, I would leave him to burn’.

Kilroy totally achieves what she sets out to do: in particular, the sequences in the forest and the beach, when our narrator temporarily loses her grip on reality, are both moving and technically brilliant. Unfortunately, for me, what she sets out to do just isn’t that interesting. I’ve read so many books that do it already. In particular, I felt aggrieved on behalf of Sarah Moss’s Night Waking, which is about simultaneously mothering an insomniac toddler and paranoid eight-year-old, and which is funnier and sharper than Soldier Sailor. I also – this book is not for me – started to feel beaten over the head with how much our narrator wants to tell us that men and women are Just Different. Soldier doesn’t understand wine, mechanics, why people care about cars; walking in the dark always makes her scared; she’s pissed off at her husband for his total obliviousness, but does nothing about it. Why doesn’t she leave him? Unlike Moss’s Night Waking, which is good on the deep unspoken sexual bond between Anna and her husband, we barely get a glimpse of what drew these two to each other in the first place. And the trouble is, the more we’re told how Different men and women are, the more Soldier’s situation starts to feel inevitable rather than oppressive.

One of the most beautiful and resonant passages in this book is near the end, on the beach:

That night I made another grave error of judgement. I tried to save a girl who had drowned some years ago, bladderwrack tangled in her hair. She drowned before you were born, seconds before you were born, as she brought you into this world… That girl, you’d have liked her, but I left her for dead. Had to. This was a woman’s job.

As well as this works in the context of Soldier’s journey, however, it left me with a bad taste in my mouth, because it returns to the old story that it’s only by having children that women really grow up. This myth of motherhood is especially persistent, I think, because some parents compare their pre-child selves to their post-child selves and think, ah, I am much more of an adult now. The problem is that, even though I don’t have children, I am not the same self I was in my twenties; I have changed too. Interestingly, I can see it in my own responses to Night Waking, which I first read in my early twenties, when I thought I wanted kids in the future. In my first review of the novel, I found Anna’s relationship with her children a bit disturbing, because she is so emotionally honest (“Good morning,” said the Tiger [Who Came To Tea]. “I’m here to symbolise the danger and excitement that is missing from your life of mindless domesticity”‘. When I re-read it in my early thirties, I was cheering Anna on, having gained a much greater appreciation of the emotional labour of care work (‘”Mummy stop it raining”, “I can’t stop it raining. Believe me, if I had supernatural powers the world would be a very different place.”) I too am a woman, no longer a girl.

This speaks to the wider literary climate that may not have created Soldier Sailor but which has certainly contributed to the many accolades it has received: the idea that these stories of motherhood are still untold. If these books continue to resonate with so many readers, of course they deserve to exist. But it’s interesting that there seems to be a sense that women without children have had their turn and now we need to hear from mothers. Indeed, most women in fiction do not have children, but this is not because they are childless or childfree, but because they haven’t had children yet. Fiction is still obsessed with the coming-of-age and the young. Many writers have noted how this shafts middle-aged and older women, but there’s a particular cost here for the one in five women who never have children. The stories of women without children past childbearing age are just not getting told. Navigating this new era of life without experiencing the sudden ‘drowning’ of motherhood but still, knowing that the seas have changed, feels increasingly like sailing uncharted waters.

I borrowed this book from my local library #LoveYourLibrary

You know how I feel about this from my comment on Goodreads, but yes, and thank you, and wouldn’t it be *fascinating* to see not only more work centering women past childbearing age, but work about such women who *haven’t had children*?! I can’t think of any. I can think of a fair few books about women in their 50s-80s (though increasingly fewer titles towards the far end of that spectrum) but virtually all of them are women with children, because the family tends to drive the drama of plot in such books. Maybe the only exception is Charlotte Wood’s The Weekend, although the women in that friendship group who are childless are also sort of pathetic, one coddling her ancient dog well past the point when she should have euthanised him, and the other reliant on past lovers for money and support.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There must be some, but whenever I think of a possible protagonist, they have random children I forgot about! Your description of The Weekend reminds me of how childlessness is treated amongst the group of younger women in Anna Hope’s Expectation. Will definitely avoid.

What I find really fascinating about this trend in fiction is that figure I quoted for childlessness has held roughly steady, at least in Britain, since WWI (we don’t have the figures for millennials yet tbf as they use 45 as the cut off age). So roughly every 1 in 5 women reaches 45 without biological children across a century that otherwise has seen massive demographic change, the rise of fertility treatment, the sexual revolution, new social attitudes to single motherhood, queer women as mothers, etc etc. What’s going on there?? But it means that anyone who tries to say that women who never have children are a new trend is just wrong.

LikeLike

Much to chew on here, thank you, and to reflect on when I read women’s fiction in future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Despite the familiar content, I’ve been enjoying this one for the voice. Then again, I’m only about 65 pages in, so perhaps it will wear thin after a while. I think by comparison you will find Reproduction fresh, even though it is also autofiction obsessed with motherhood; it’s the sort of book I wish the WP would have recognized. Sigrid Nunez is childfree and thus most of her narrators are as well. I share your frustration that women without children don’t represent nearly 1/5 of the stories out there; I’m keen to find more role models. I do think the birth rate will plummet in our generation and the ones after, though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I didn’t love the voice as such because I didn’t warm to the protagonist, but there’s no doubt Kilroy’s a very good writer.

I’ll be fascinated to see what happens when we get those stats for millennials. My hunch is that millennials in Britain have tended to delay childbearing rather than remain childless en masse, but we’ll see if that 1 in 5 figure shifts…

LikeLike

Thanks for this interesting take on the book. I was blown away by it. Perhaps I am just not reading widely enough but I can’t recall another book that reflects the experiences of early motherhood so viscerally but also accurately. I hope more men read it. Of course, a reader’s take will often reflect their own lived experiences. I thought the writing style brilliant – intense but always engaging.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree, Kilroy is clearly a very talented writer and I think it would be great for more men to read this book! The close first-person narration is more immediate here, but I’ve read a number of similar (+ very good) takes on early motherhood from Sarah Moss’s Night Waking back in 2009 to Kate Murray-Browne’s One Girl Began in 2024, which I liked for its more expansive sense of hope and possibility. This one has clearly resonated very, very deeply with many readers, though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really loved this, but I too much preferred Night Waking, which is one of the best depictions of motherhood I have ever read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh interesting – glad it wasn’t just me!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Women’s Prize for Fiction, 2024: Final Thoughts | Laura Tisdall

Very interesting, much to think about there. I don’t recall seeing much if anything featuring childless women over 45 as central characters, though there are a fair few in Iris Murdoch (and I’m working on a paper for the IM Soc Conference at the moment talking about aging and reader response theory so will keep a special lookout). Certainly when old women are alone in books it’s because they are estranged from their families rather than having not had childern, I feel. The most visceral baby-and-mother book I’ve read was Enid Bagnold’s The Squire, very milky. But then I do tend to avoid the topic.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting – I’ve not read any Iris Murdoch. So cool you’re speaking at the conference!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I did a couple papers a few years ago on my own reading then my independent study on IM and book groups and missed a couple of conferences but had an idea for this one so submitted am abstract and here I am, preparing a new paper! I think you might like IM. I’d recommend Nuns and Soldiers to you …

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Love Your Library, June 2024 | Bookish Beck