I’ve been trying to read more science fiction lately, but am uncomfortably aware that as a relative stranger to the genre, it’s taking me some time to find my niche, which has led to some disastrous choices (Joe Haldeman’s horribly misogynistic and homophobic The Forever War being one of them). In contrast, Ted Chiang’s Stories of Your Life and Others is certainly worth reading. These weird, original and cerebral short stories were, on the whole, not quite my thing, but at least I now feel I’m heading in the right direction. Chiang’s stories often engage the mind more than the heart, and while I was impressed by his imagination and invention, I struggled to stop thinking about what I was reading and start feeling. ‘Understand’, which makes a very brave attempt to convey the experience of an ordinary man who starts to acquire super-intelligence, was a case in point – although Chiang’s handling of this topic, for my money, is still far superior to the more famous Flowers for Algernon. Similarly, ‘Division by Zero’, which stars a mathematician who discovers an equation that seems to undermine the foundations of mathematics as we know it, impressed me, but didn’t enthral me. It’s telling that Chiang’s wonderful Story Notes were often better than the stories themselves: for ‘Division by Zero,’ for example, he writes: ‘A proof that mathematics is inconsistent, and that all its wondrous beauty was just an illusion, would, it seemed to me, be one of the worst things you could ever learn.’ He makes a real stab at conveying both the elegance of formal proofs and the horror of their disintegration to those of us who are less mathematically-minded, but I don’t think he quite pulls it off.

I’ve been trying to read more science fiction lately, but am uncomfortably aware that as a relative stranger to the genre, it’s taking me some time to find my niche, which has led to some disastrous choices (Joe Haldeman’s horribly misogynistic and homophobic The Forever War being one of them). In contrast, Ted Chiang’s Stories of Your Life and Others is certainly worth reading. These weird, original and cerebral short stories were, on the whole, not quite my thing, but at least I now feel I’m heading in the right direction. Chiang’s stories often engage the mind more than the heart, and while I was impressed by his imagination and invention, I struggled to stop thinking about what I was reading and start feeling. ‘Understand’, which makes a very brave attempt to convey the experience of an ordinary man who starts to acquire super-intelligence, was a case in point – although Chiang’s handling of this topic, for my money, is still far superior to the more famous Flowers for Algernon. Similarly, ‘Division by Zero’, which stars a mathematician who discovers an equation that seems to undermine the foundations of mathematics as we know it, impressed me, but didn’t enthral me. It’s telling that Chiang’s wonderful Story Notes were often better than the stories themselves: for ‘Division by Zero,’ for example, he writes: ‘A proof that mathematics is inconsistent, and that all its wondrous beauty was just an illusion, would, it seemed to me, be one of the worst things you could ever learn.’ He makes a real stab at conveying both the elegance of formal proofs and the horror of their disintegration to those of us who are less mathematically-minded, but I don’t think he quite pulls it off.

One of the key problems I had with stories like ‘Division by Zero’ and ‘Understand’ was that they seemed to be taking place in a white void; there is little physical description to root the reader. But Chiang is absolutely capable of intricate world-building. ‘Seventy-Two Letters’ is fabulously rich in pseudo-historical detail, as he invents a version of nineteenth-century England where automatons are an ordinary part of life. Similarly, his ‘Hell is the Absence of God’ is consistently funny, despite its dark subject-matter, as it imagines a world where angelic visitations are commonplace and Hell is frequently visible. When the angel Nathaneal makes ‘an appearance in a downtown shopping district… sixty-two people received medical treatment for injuries ranging from slight concussions to ruptured eardrums to burns requiring skin grafts. Total property damage was estimated at $8.1 million, all of it excluded by private insurance companies due to the cause.’ Sometimes, Hell manifests itself: ‘the ground seemed to become transparent, and you could see Hell as if you were looking through a hole in the floor.’ For me, the only story that was an unqualified success (partly because Chiang sets such impossibly high bars for himself to clear) was ‘Tower of Babylon’, where Chiang manages to harness another incredibly interesting concept into a satisfying ending.

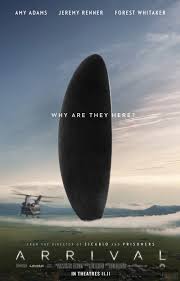

But the story I really want to discuss is ‘Story of Your Life’, which was the inspiration for the widely-praised 2016 film Arrival. [The rest of this review will feature significant spoilers for both Arrival and ‘Story of Your Life.’ You have been warned!] Anyone who has spoken to me about Arrival will know how frustrating I found it. The basic premise is great: a linguist, Louise Banks, is hired to learn the language of a group of aliens who have recently landed on Earth. The film is also great – until the final half hour. I found the resolution of Arrival totally unsatisfying, and to be honest, I’m amazed there hasn’t been a bigger critical backlash. (It rests on the – to me, absurd – idea that by learning a language, your brain can somehow acquire the ability to see the future. How???) We discover that the ‘flashbacks’ Louise has been having throughout the film to the life and death of her daughter are in fact ‘flashforwards’ – and are asked to accept that, even though she now has this foreknowledge, her choices aren’t going to change. Finally, as Debbie Cameron has argued, the film relies on traditional gender roles; Louise saves the world because of her nurturing, empathetic personality, which is linked to her future role as a bereaved mother.

But the story I really want to discuss is ‘Story of Your Life’, which was the inspiration for the widely-praised 2016 film Arrival. [The rest of this review will feature significant spoilers for both Arrival and ‘Story of Your Life.’ You have been warned!] Anyone who has spoken to me about Arrival will know how frustrating I found it. The basic premise is great: a linguist, Louise Banks, is hired to learn the language of a group of aliens who have recently landed on Earth. The film is also great – until the final half hour. I found the resolution of Arrival totally unsatisfying, and to be honest, I’m amazed there hasn’t been a bigger critical backlash. (It rests on the – to me, absurd – idea that by learning a language, your brain can somehow acquire the ability to see the future. How???) We discover that the ‘flashbacks’ Louise has been having throughout the film to the life and death of her daughter are in fact ‘flashforwards’ – and are asked to accept that, even though she now has this foreknowledge, her choices aren’t going to change. Finally, as Debbie Cameron has argued, the film relies on traditional gender roles; Louise saves the world because of her nurturing, empathetic personality, which is linked to her future role as a bereaved mother.

How does ‘Story of Your Life’ deal with the same basic plot line? On the whole, much better. It turns out that much of the plot that fills the film’s final half hour was added – which means that Chiang completely avoids the gendered implications that Cameron dissects. He also faces the question of Louise’s motivations head on, which made me feel much more convinced that knowing the future wouldn’t necessarily entail changing the future: ‘What if the experience of knowing the future changed a person?’ she narrates. ‘What if it evoked a sense of urgency, a sense of obligation to act precisely as she knew she would?’ This model of how gaining new knowledge might actually alter the way somebody thinks worked much better, for me, than the idea that the aliens’ language confers the power of prerecognition. (Chiang keeps this concept, but – partly because the linguistics in the story is so much more complex than the linguistics in the film – it didn’t feel quite as jarring). I also loved the way he dealt with the ‘flashforwards’, narrating in a mix of tenses that neatly demonstrate on the page how a very simple alteration in language can mess with your head. ‘I remember one afternoon when you are five years old,’ Louise narrates, jarringly, to her future daughter, or ‘I remember one day during the summer when you’re sixteen.’ Like so many of the stories in ‘Stories of Your Life and Others’, ‘Story of Your Life’ bites off a bit more than it can chew – but it’s exhilarating anyway.

***

Speaking of language, I have some very brief thoughts about Laura Kaye’s English Animals, which focuses on Mirka, a lesbian from Slovakia who starts work in an upper-class English household and finds herself embroiled in an affair with one of her employers, the bicurious Sophie. Frankly, I hated the novel when I first read it; I thought it was incredibly badly-written, with a very black-and-white morality (Mirka good, English upper classes bad – and while I am hugely sympathetic to this from a political perspective, it didn’t make for very interesting fiction!). I recently read an interview with Kaye which explains why I found the language of the novel so lifeless. She explains that she was imagining Mirka narrating in English, with all the second-language limitations and mishaps that entails. ‘Another concern,’ she writes, ‘was that Mirka might come across as less intelligent with her deficient language, while the English people seemed more sophisticated and educated by comparison. I hope she doesn’t – in my mind she comes across as far more intelligent, brave and imaginative than anyone else in the book’. Unfortunately, I did find Kaye’s stylistic choice alienating, and I think I would have been much more sympathetic to Mirka as a character if she had just been allowed to narrate in the same way that anyone narrates in their own head. Furthermore, while Mirka is clearly a far more admirable figure than anybody else in the book – and it is refreshing to read a novel narrated by a lesbian who is utterly sure about her own sexuality – this is precisely what made her an uninteresting protagonist. I wasn’t surprised to read that English Animals began as a series of scenes told from Sophie’s point-of-view. Sophie is selfish and weak, but I wanted to read about her internal conflict much more than I wanted to read about the idealised Mirka. Like Paul Kingsnorth’s The Wake, this is another novel where complicated linguistic ambitions don’t come off.

Speaking of language, I have some very brief thoughts about Laura Kaye’s English Animals, which focuses on Mirka, a lesbian from Slovakia who starts work in an upper-class English household and finds herself embroiled in an affair with one of her employers, the bicurious Sophie. Frankly, I hated the novel when I first read it; I thought it was incredibly badly-written, with a very black-and-white morality (Mirka good, English upper classes bad – and while I am hugely sympathetic to this from a political perspective, it didn’t make for very interesting fiction!). I recently read an interview with Kaye which explains why I found the language of the novel so lifeless. She explains that she was imagining Mirka narrating in English, with all the second-language limitations and mishaps that entails. ‘Another concern,’ she writes, ‘was that Mirka might come across as less intelligent with her deficient language, while the English people seemed more sophisticated and educated by comparison. I hope she doesn’t – in my mind she comes across as far more intelligent, brave and imaginative than anyone else in the book’. Unfortunately, I did find Kaye’s stylistic choice alienating, and I think I would have been much more sympathetic to Mirka as a character if she had just been allowed to narrate in the same way that anyone narrates in their own head. Furthermore, while Mirka is clearly a far more admirable figure than anybody else in the book – and it is refreshing to read a novel narrated by a lesbian who is utterly sure about her own sexuality – this is precisely what made her an uninteresting protagonist. I wasn’t surprised to read that English Animals began as a series of scenes told from Sophie’s point-of-view. Sophie is selfish and weak, but I wanted to read about her internal conflict much more than I wanted to read about the idealised Mirka. Like Paul Kingsnorth’s The Wake, this is another novel where complicated linguistic ambitions don’t come off.

I received a free proof copy of English Animals from the publisher for review.

It’s funny I should see this after just having watched Arrival. (Especially because I rarely get the chance to watch a relatively new movie.) I watched it with my teenage son and daughter and so enjoyed the experience, but I did feel confused in the end as to exactly what went on. It sounds like the book makes it more clear. I didn’t even know there was a book!

A question we were left with was, how did the aliens help humanity? When asked what their purpose was they said to help humanity, because they would need humanity’s help in 3000 years. We weren’t quite sure how they helped!

LikeLike

I remember being confused about this as well! The short story didn’t clarify that for me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Too bad!

LikeLike

Pingback: 2019 Reading Plans | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: 20 Books of Summer, #14: A People’s Future of the United States | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: 20 Books of Summer, #17: Exhalation | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: Some of My Favourite Short Stories | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: My thoughts on… The 100 Most Popular Sci-Fi Books on Goodreads – Annabookbel

Pingback: March Superlatives | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: Bay Tales 2023: Crime Writing By The Sea | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: Three SFF Novels About New Forms of Intelligence: The Mountain in the Sea, Cold People & The Book of Phoenix | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: #SciFiMonth: Butler, Doctorow, Older | Laura Tisdall