The Women’s Prize for Fiction shortlist will be announced today, Wednesday 24th April, at 8am – so I’m squeezing in a couple more longlist reviews just in time!

I was attracted to 8 Lives of A Century-Old Trickster, Mirinae Lee’s debut novel, by its blurb: an elderly woman, Ms Mook, who is living in a nursing home in the demilitarised zone separating North and South Korea, tells the stories of her eight unbelievable lives. It turns out, as other reviewers have noted, that this novel has been patched together from five previously published short stories, with two others, plus this framing narrative, added to pull it together. Unfortunately, I could really see the traces of these stories’ origins, which made 8 Lives feel repetitive and unsatisfying, despite some strong sections. We hear about the ‘comfort women’ forced into working in a Japanese brothel in Indonesia during the Second World War; a child who poisons her abusive father in North Korea in the 1930s; and a young North Korean woman who flees to China post-war and seeks help from an American pastor. The stand-out for me was ‘Me, Myself and Mole’, set in 1955: a North Korean man’s wife returns after the war, having been kidnapped by Japanese soldiers, but he slowly realises that she is not who she seems to be. This sets up a wider theme of double lives and deception that runs throughout the novel. But you can still see the joins. Later stories spell out too clearly what happened in earlier stories, and Lee ultimately tells us how all these stories fit together, even though it was pretty obvious to me by the midpoint. (The chronology, however, is still off: Ms Mook claims to be nearly a hundred years old but this doesn’t seem to line up, particularly with her adopted daughter’s timeline; trouble is, Lee doesn’t handle this confidently enough to make it clear whether this is another of Ms Mook’s fantasies or fuzzy maths.) This isn’t a bad novel, but I don’t think it belongs on prize lists.

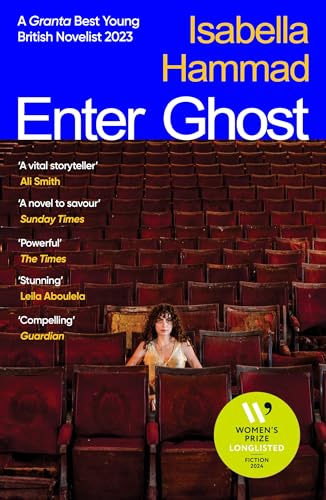

I’m still halfway through Isabella Hammad’s Enter Ghost, so this won’t be a full review, but it stands out to me as one of the stronger entries on the longlist. Sonia is a Dutch-Palestinian actor who grew up in London; in her late thirties, after the end of a love affair, she goes to visit her older sister Haneen in Haifa. Despite Sonia’s initial resistance, she finds herself being cast in a production of Hamlet in the West Bank, directed by Mariam, whose brother is a politician under baseless investigation from the Israeli authorities. Hammed handles the intricacies of Sonia’s family beautifully, teasing apart several layers of guilt and displacement. How do Palestinians with Israeli passports who live within ‘ ’48’ – the Palestinian land taken in 1948 that ‘is today considered to comprise the modern state of Israel’ – relate to Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza? How can Sonia, with her British passport, claim to belong even in ’48, despite having spent all her childhood summers in Haifa? But is Haneen, who controversially teaches at an Israeli university, any less of an outsider? I’m particularly appreciating both the taped and spoken scenes that are written as play scripts, inviting the reader to consider the true weight of what each character is saying. And this is, of course, a horribly timely book in the face of the ongoing genocide in Gaza. But so far, Enter Ghost strikes me as a novel that’s almost too carefully crafted. Its themes are not clunky but they are very mappable: it would be easy to write an essay on how Sonia is the ghost re-entering her ‘home’ land where she plays a mother despite unwillingly being childless in a play that is about a police state etc etc. I haven’t yet emotionally connected with her or with the other characters, so I feel, at the moment, as if this is one to admire, and to learn from, rather than to love.

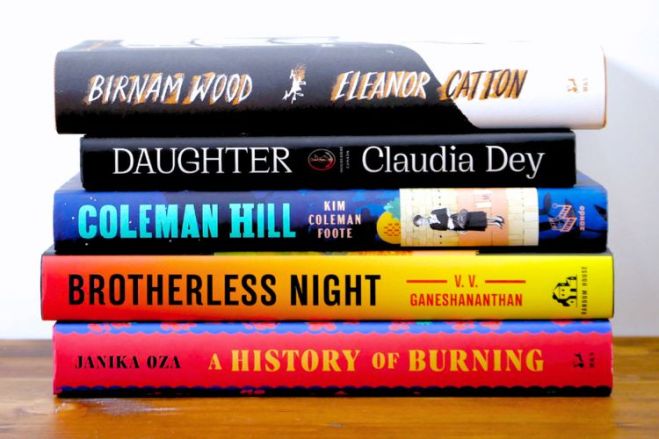

Having only read six books from the longlist, I won’t be making any predictions this year, but here are my rankings of the ones I have read, with links to my other reviews.

- Brotherless Night by V. V. Ganeshananthan

- Enter Ghost by Isabella Hammad

- The Blue, Beautiful World by Karen Lord

- 8 Lives of A Century-Old Trickster by Mirinae Lee

- In Defence of the Act by Effie Black

- River East, River West by Aube Rey Lescure

Overall, my reading has confirmed my first impression: this list is very meh. I was underwhelmed by most of what I read, and I haven’t even touched the longlisted novels that didn’t immediately appeal to me. Given that a lot of the picks I’ve read are obviously judges’ wild card choices (Lord, Black, potentially Lee), I doubt many of these will be shortlisted, and therefore doubt that I’ll have the energy to read another 4-5 books from this list.

On the flip side, the only ones I can muster up any enthusiasm for seeing on the shortlist are Brotherless Night and maybe Enter Ghost – neither of which I totally loved.

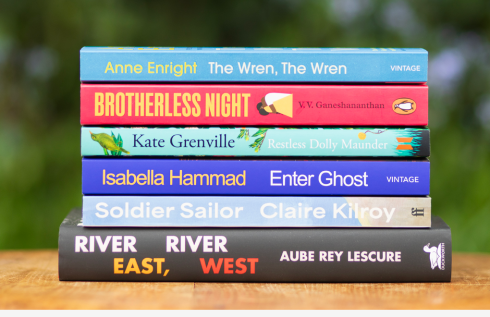

And the Women’s Prize for Fiction Shortlist 2024 is….

OK, so this is totally unverifiable… but I was just saying to my friend that Hammad, Ganeshananthan, Kilroy and Enright surely have a good shot, and the other two are wild cards… and that’s what we’ve got. Given the longlist, I don’t hate this. Obviously we all know my thoughts on the Lescure, so I’d have swapped that one out, but otherwise, this looks like the best of a bad bunch.

I’ve read three already, of course, and I will now probably read the Kilroy, but I don’t think I’ll bother to read the whole list. Neither Grenville nor Enright have lit my heart on fire in the past.

What are your thoughts on the Women’s Prize Shortlist 2024?