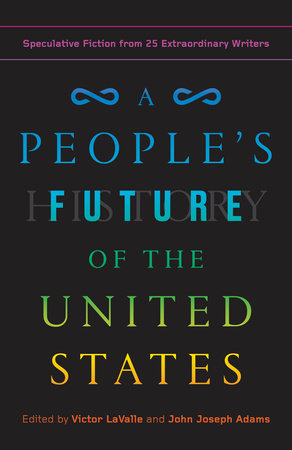

Victor LaValle’s and John Joseph Adams’s edited collection of speculative fiction, A People’s History of the United States, has a brilliant premise. As LaValle explains in his introduction, the title riffs on Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States (1980), which, in the words of the jacket copy, was the first book ‘to tell America’s story from the point of view of – and in the words of – America’s women, factory workers, African-Americans, Native Americans, the working poor, and immigrant laborers.’ Whether or not this historiographical claim is true, LaValle and Adams used this famous text as a jumping-off point for this collection. They, LaValle writes, ‘decided to ask a gang of incredible writers to imagine the years, decades, even the centuries, to come. And to have tales told by those, and/or about those, who history often sees fit to forget.’ The jacket copy of this book doubles down on LaValle’s framing, suggesting that: ‘Knowing that imagining a brighter tomorrow has always been an act of resistance, [the editors] asked for narratives that would challenge oppressive American myths, release us from the chokehold of our history, and give us new futures to believe in.’

My disappointment with the majority of this collection, therefore, stems both from the fact that most of the stories here don’t do this, and the fact that the stories that do are almost always head and shoulders above their predictable dystopian counterparts. While many of the snatches of misery here are well-written, do we really need another set of futures that envisage the bureaucratic oppression of trans and non-binary people (A. Merc Rustad’s ‘Our Aim Is Not to Die’), imagine high-tech gay conversion therapy (Violet Allen’s ‘The Synapse Will Free Us From Ourselves’), allow no access to contraception or abortion (Justina Ireland’s ‘Calendar Girls’) or predict the reinstatement of enslavement (Lesley Nneka Arimah’s ‘The Referendum’*)? Not only are these stories pessimistic, they are usually unimaginative; it doesn’t take much to think of a future where things are uniformly worse. But history doesn’t usually march towards progress or slide towards despair; realistic futures will be a mix of both. Moreover, these stories usually have very little to say about identity other than that we shouldn’t oppress others; to me, the diversity, especially around LGBT+ identities, often feels tick-box rather than significant (for example, in Seanan MacGuire’s ‘Harmony’).

*I still love Arimah’s writing, though: for better work by her, both realistic and speculative, check out her collection, What It Means When A Man Falls From The Sky.

These stories, however, still work on some level; for me, the absolute failures in this collection – which were in the minority, but still all too frequent – were the stories where the writer seemed to have misunderstood how fiction functions. These stories spelt out their messages so simplistically that they left no space for creativity. By far the worst was Ashok K. Banker’s ‘By His Bootstraps’, which imagines a future where a president who strongly resembles Donald Trump has used a bioweapon meant to return America to its original genetic purity. In case you can’t guess where this is going, Banker has one of the characters tell you: ‘Mr President, you gave the order to deploy Operation Clean Sweep because you thought – we all did – that it would be a clean sweep of our country’s racial diversity, restoring America to the white Christian nation we all believed it once had been. But that was a myth. America has always been an ethnically diverse myth, a melting pot of races and cultures.’ Not only is this terrible writing, it also seems strikingly naive about how white supremacy functions; as if white supremacists would realise the error of their ways if they attended more history lessons.

Amongst all this, however, are some absolute stars. Malka Older’s ‘Chapter 5: Disruption and Continuity (Excerpted)’ is simply brilliant, recalling Ted Chiang’s ‘Story of Your Life’ in how it plays with tenses to deploy its central concept. Readers may have different interpretations of this story, which is written in the style of an academic monograph, but for me, it seemed to come from a future where time travel has become an accepted research method for historians, leading to this kind of baffling but glorious analysis by ‘futurists’:

“Civil society” will become, in the absence of strong political institutions, just “society”, while without coherent corporations “social media” will become just “media”. While we can describe these transitions, from a distance, as neutral changes or even positive outcomes of creative destruction, it is important to remember that for people living in that time, such drastic shifts are disorienting and frightening.

I loved the idea of getting away from teleological narratives of ‘everything got better’ or ‘everything got worse’ by imagining historians as observers of a range of past and future time periods, able to pity or admire the future as much as the past. Older takes the challenge posed by the editor head on, and her story seems to frame the whole collection.

Similarly, I appreciated Omar El Akkad’s ‘Riverbed’, which envisages a future US making reparations for the forced displacement and internment of its Muslim citizens, because of El Akkad’s willingness to imagine a scenario that isn’t wholly negative or positive. The assertiveness of its main character, Khadija, at the airport and with her taxi driver, subtly makes the point that she’s operating in very different circumstances than Muslim women do today, but the horrors of her past show how easily we could tip into this kind of atrocity. El Akkad’s American War, which I read for last year’s 20 Books of Summer, didn’t really work for me, but this story underlined what a promising writer he is. Daniel H. Wilson’s ‘A History of Barbed Wire’, which imagines a reservation built by the Cherokee Nation with a wall to keep refugees out, also strikes an interesting balance.

Finally, the editors irritatingly group a number of the best stories near the end of the collection. Charles Yu’s ‘Good News Bad News’ and N.K. Jemisin’s ‘Give Me Cornbread Or Give Me Death’ both use humour to great effect; Yu’s story, in particular, slips between satire and chilling realism as he quotes from invented news stories about racist robots, sentient trees and an automated Congress. Jemisin has fun with a more fantastic tale of dragons who are persuaded not to feed on the populace by being given various spicy vegetable dishes instead. G. Willow Wilson’s ‘ROME’, though not as original as other offerings, tells an enticingly human story about a group of people trying to finish their automated English tests while the street burns around them because voters didn’t want to pay taxes for firefighters.

However, the stand-out entry in A People’s Future of the United States is probably the very last one. Alice Sola Kim’s ‘Now Wait For This Week’ (read it here) flips the familiar Groundhog Day trope to tell the repeating week from the perspective of the time traveller’s perplexed friends. This both works brilliantly on a story level and helps Kim illuminate wider narratives about the endless ‘Me Too’ media cycle that lacks real justice, because it doesn’t tackle the structural causes of men’s behaviour. Kim also trusts her readers to join the dots without having everything spelt out for them, both structurally and thematically. Speculative fiction writers, this is how it’s done: more like this, please?

Ahhhhh this collection seemed so promising and it’s so disappointing to see that the mark was mostly missed. Although I love the sound of Omar El Akkad’s, Daniel Wilson’s, and Alice Sola Kim’s stories in particular.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know, I was disappointed but on the other hand, the good stories are really good. You can read Kim’s online if you don’t want to get the whole collection. It’s also helped me to find some new diverse SF authors to read: I want to check out more by Kim, Yu and both Wilsons.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds so interesting! It’s a shame many of the stories were underwhelming, but I’m glad there were at least a few gems that made it worthwhile.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m definitely glad I read it! It’s helped me prioritise future reading as well…

LikeLike

It sounds like a lot of this really missed the mark, which is a shame as the premise is so good.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s also just a beautiful book. I love the cover and the typesetting.

LikeLike

Pingback: 20 Books of Summer, #18, #19 and #20: Friday Black, All Is Song and Free Food for Millionaires | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: 20 Books of Summer 2019: A Retrospective | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: Some of My Favourite Short Stories | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: Hit and Miss: Two Short Story Collections | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: #SciFiMonth Reading Plans | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: Words Weekend, Sage Gateshead, December 2019, & Weekend Reading | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: #SciFiMonth Reading, 2020 | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: #SciFiMonth: Yu and Binge | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: ‘An obvious, simple evil’: Chain-Gang All-Stars by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: Reading Plans for SciFi Month/Novellas in November! | Laura Tisdall