There have been a lot of popular musings published on the Arctic and Antarctic, as anybody who goes to the Scott Polar Institute’s library in Cambridge will know, as they’ve collected all of them. From historical takes such as Sarah Moss’s The Frozen Ship or Francis Spufford’s I May Be Some Time, to personal stories of time spent in one of the continents such as Gavin Francis’s Empire Antarctica or Sara Wheeler’s Terra Incognita, there’s no shortage of accessible non-fiction for readers fascinated by the farthest north or farthest south. And within this glut, ice forms a recognisable sub-category, from Stephen Pyne’s classic Ice: a journey to Antarctica (1986) to more recent publications such as Veronika Meduna’s Secrets of the Ice (2005) and Joanna Kavenna’s The Ice Museum (also 2005). What, then, makes Nancy Campbell’s The Library of Ice stand out? Because as a dedicated reader of this sub-genre, I can tell you that stand out it does.

Perhaps it’s Campbell’s eclectic approach to her subject-matter. Rather than focusing on either the Arctic or Antarctic, she seeks out ice wherever she can find it – whether that’s a curling rink in Scotland, where she has a fascinating conversation about how the smoothness of the ice is maintained, or glaciers in Switzerland. She hits some familiar notes – the discussion of Antarctic ice cores, and how they preserve the history of the atmosphere because of how the chemical make-up of the ice changes as you drill further down, usually pops up in texts like this – but to be honest, I never get tired of hearing about them.

Meanwhile, Campbell’s take is poised elegantly between a personal account of her own travels and a more observational consideration of the natural history of ice. We actually find out very little about Campbell’s present life – she alludes to money troubles, and there’s one night where she sleeps propped up against the door of an airport toilet that she mentions as if it’s nothing out of the ordinary. (Her life seems to be held together by literary grants, which are notoriously capricious – she’s currently the UK Canal Laureate for 2018, which I think is fantastic. I’d love to read anything she writes about canals, having had my interest sparked by Alys Fowler’s Hidden Nature). On the other hand, Campbell doesn’t always remove herself completely from the story – she tells us, for example, about her childhood love of the Noel Streatfeild novel White Boots, about two girls who are learning to ice-skate. I re-read this over and over again when I was little, and it was lovely to revisit it, although I have to admit (as I know nothing about ice-skating) being somewhat dismayed that the ‘figures’ that our poor protagonists painstakingly practice in 1951 were already declining in importance in the sport by that time, and were abolished altogether by 1990.

Finally, Campbell’s book simply stands out because it’s so much better written than other books on the subject. There’s something about the Arctic and Antarctic that seems to tempt writers into some of the worst purple prose, woven into paragraphs that go off on endless tangents (with some honourable exceptions, such as Francis’s Empire Antarctica, which is nicely straightforward). Campbell doesn’t fall into these traps, spending less time on descriptions of the landscape than she does getting into the nitty-gritty of the things she finds out, whether that’s the experience of living in an isolated community in Greenland or researching early texts on snowflakes in the Bodleian. This makes her text dense – I found that I wanted to read it slowly to take in all the information – but it never becomes confusing or too technical. She’s giving a talk on this book at the Lit and Phil in Newcastle later in November, and I can’t wait to hear what she says.

I received a free proof copy of this book from the publisher for review.

Luke Turner’s Out of the Woods uses Epping Forest as a backcloth for the exploration of his own confusing psyche: quoting St Augustine, he reflects that the inner world is ‘a limitless forest, full of unexpected dangers.’ As a bisexual man, Turner has often felt caught between two worlds, and as this memoir proceeds, we discover that the pull he feels towards spontaneous and risky sexual encounters can, he believes, be traced back to early abusive experiences with older men as a teenager. The forest itself feels like neither one thing or another; not a truly wild place, as it is so close to the suburbs of London (and Turner describes some of the decaying, yet expensive houses of these suburbs in vivid detail), and yet a place that has long been visited by the city’s inhabitants for behaviour that has been viewed as outside social bounds. Turner reflects on the men convicted for public indecency in the forest, and how it is still used as a male cruising ground; he finds out that his own ancestors had a child out of wedlock, and speculates that it was conceived in Epping.

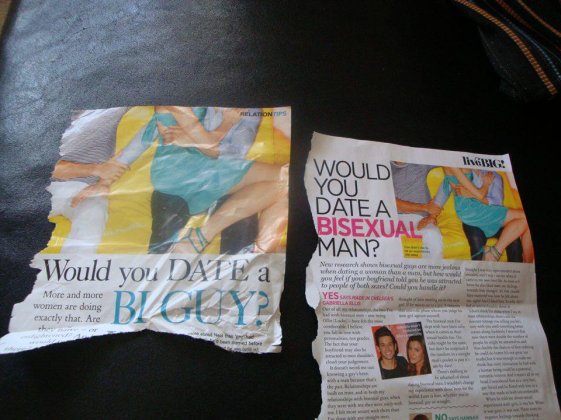

This is one of those memoirs when I feel I have to distinguish carefully between the voice and the person. I have every sympathy for Turner’s struggle with his sexuality, and for what he suffered in his early years. As he rightly points out, bisexual men are still marginalised in a way that gay men are not: many people still persist in believing that they don’t exist or in stereotyping them as kinky, polygamous hedonists who can never be appropriate long-term partners – especially in heterosexual relationships. This is particularly evident in chick lit and in women’s magazines, as the two articles below (Glamour, 2012 and Cosmo, 2013) indicate:

And yet, despite the fact that Turner highlights these important issues, I did not feel that Out of the Woods succeeded as a memoir. I’m afraid I found it self-indulgent, and the writing often awkward and overwrought. Unlike Campbell, Turner is front and centre all the time (no chance of missing his struggles with housing), and he fails to weave his personal experiences satisfactorily into a wider narrative about woodlands, sexuality, and state policing. I also found the lack of explicit recognition of male privilege a little frustrating; as I’ve said above, bisexual men face particular and serious prejudice, but at certain points in this memoir, Turner makes it sound as if they are the most radical, binary-breaking, properly oppressed group in history, which isn’t a label I think should be applied to any social group. And while Turner picks up on some interesting facts about woodland, such as the ability of trees to communicate with each other through networks of moss (see Suzanne Simard’s 2016 TED talk for more), there are much better books out there on the woods, notably Sara Maitland’s Gossip From The Forest. So for me, a really groundbreaking book about bi men has yet to materialise.

I received a free proof copy of this book from the publisher for review. It’s out in January 2019.

I am hooked on polar-themed books, too. (Of the ones you mention, I’ve read Kavenna and Wheeler.) I started The Library of Ice last weekend and got to about 6% before setting it aside, but I’ll go back to read it slowly and steadily over the course of the winter. Her writing is very enjoyable – it reminds me of Gretel Ehrlich’s in This Cold Heaven. [I fancied a print proof and wrote to proofs@simonandschuster.co.uk but never heard back, so I’m reading this from NetGalley instead. How did you manage to get their attention?] And I live by a canal, so I love that she now has that role!

The premise of Turner’s memoir appealed to me, but after reading your review I think it’s one I’ll wait and read from the library, if at all. Ever since H Is for Hawk there have been loads of these nature-y memoirs where someone picks an aspect of their life in which they feel different and then explores that alongside travel/nature writing. Sometimes it works well, but sometimes the nature of the difference or the depth of thought about it doesn’t really warrant a full book. I don’t know if you’ve found that too?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had a NetGalley proof, as well – I just call it a proof copy so I can use the same boilerplate for all my reviews, sorry for confusion! I would love a print copy of this one, I imagine it’s beautiful. A friend of mine works on a poetry magazine and they recently used a piece of Campbell’s art for the cover. I haven’t heard of Ehrlich – I’ll look her up.

I agree – I think these kind of nature memoirs are really difficult to pull off. I wasn’t completely sold on H is for Hawk and I loved the nature bits of Amy Liptrot’s The Outrun, but didn’t get on with the personal bits at all.

LikeLike

Okay, gotcha. I just thought Scribner were ignoring me 😉

I felt similarly about The Outrun.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Overstory (Richard Powers) and Unsheltered (Barbara Kingsolver) | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: 2018 in Books: Commendations and Disappointments | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: Farewell to Winter with Some Snowy and Icy Reads – Bookish Beck

Pingback: My Top Ten Books of 2020 | Laura Tisdall

Pingback: April Superlatives, 2023 | Laura Tisdall